A STRATEGY FOR THE INTERMARIUM

Making The Intermarium: Why The Advantages Surpass The Challenges

The re-emergence of the Intermarium concept — a federation encompassing Central European countries — poses a compelling argument in the geopolitical and economic realms. While critics argue that the idea is impractical due to various challenges, the evidence strongly suggests that the benefits of such a federation outweigh the drawbacks.

By creating a cohesive and unified Central European bloc within the EU, the Intermarium can streamline decision-making, reduce internal conflicts, and thereby enhance the EU’s effectiveness. By providing a counterbalance to other global powers, the Intermarium could significantly contribute to turning the EU into a geopolitical superpower, capable of asserting its interests and values more effectively worldwide.

We will explore how an Intermarium federation could serve as a catalyst for sovereignty and self-determination among Central European nations, examining the balance of power between nations like Russia and Germany. Furthermore, we will probe the sociocultural dimensions, including existing legal frameworks, that make the proposal viable. We will also scrutinize the strategic advantages an Intermarium could offer, not only in economic terms but also as a unified military force, before assessing its impact on the existing international order.

I. Simplifying European Governance Through Regional Integration

The European Union is often criticized for its convoluted governance structures and bureaucratic red tape, which frequently result in decision-making delays and a lack of cohesive policy implementation. This criticism is not without merit; the EU consists of 27 member states, each with its own set of interests and policy objectives. The inherent complexity in governing such a diverse array of nations has led to calls for federalization solutions. In this context, the proposition of a Central European federation emerges as a viable, simplified alternative that could potentially rectify these governance issues.

Take, for example, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Designed to provide financial support to farmers, the policy has often been criticized for its inefficiency and for benefiting larger, wealthier states like France and Germany disproportionately. In 2020, France received around €7.2 billion from the CAP, while Poland, despite having a similar amount of arable land, received about €3.5 billion. The complexities of decision-making within the EU framework often make it difficult for smaller or less influential countries to modify such policies to better suit their needs.

By contrast, a federation of Central European countries would represent a smaller and more streamlined entity. It would allow for quicker decision-making, as fewer parties would be involved in the governance process. Additionally, there would be a greater degree of shared interests among these geographically and culturally closer states.

These nations already exhibit more aligned economic priorities. Their economies are not as heavily reliant on high-value manufacturing sectors, as is the case with Germany, or on financial services, as with the United Kingdom before Brexit. Such economic alignments can simplify budget allocations and policy focus in a federal setup.

The linguistic and cultural similarities among Central European countries offer distinct advantages in governance. These commonalities could reduce communication barriers and simplify diplomatic negotiations, thereby accelerating policy decisions. High levels of English proficiency and shared cultural values, such as a strong sense of “solidarity,” further enable streamlined interactions, making a Central European federation more feasible and efficient.

While a full federalization model at the EU level remains contentious and requires sweeping constitutional changes, a federation within Central Europe could be a less controversial and more readily acceptable step. This would act as a proof-of-concept for other EU nations contemplating deeper integration. It would also serve as a test case for addressing issues of sovereignty, which is one of the major hurdles in the EU-wide federalization debate.

The concept of a Central European federation emerges not merely as a theoretical idea but as a pragmatic solution to the challenges of governance complexity that plague the EU. With an aligned set of economic priorities and cultural commonalities, such a federation could serve as an exemplar for efficient governance, potentially providing a simplified, more effective model for regional integration.

II. Limited Corruption Relative to Western Standards

One frequent argument against the formation of a Central European federation concerns the perceived levels of corruption in the region. However, it is essential to consider this issue relative to existing governance standards in established Western countries. In doing so, the corruption problems in Central European countries appear not only manageable but also not significantly worse than those in France or Germany.

Recent scandals, such as the one involving former French President Nicolas Sarkozy who was found guilty of corruption and influence-peddling in 2021, suggest that even established Western European democracies are not immune to corruption at the highest levels of governance, to say the least. In 2018, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy allegedly received €300,000 for delivering a conference in Russia, during which he spoke favorably about Russian President Vladimir Putin. Furthermore, still in 2019, Tracfin, the French agency responsible for combating financial crimes, disclosed that Sarkozy had entered into a consulting contract with a Russian firm for a sum of €3 million. François Fillon, who served as the Prime Minister of France from 2007 to 2012, is also a compelling example of corruption among the French political elite. Initially considered a strong contender for the French presidential election in 2017, Fillon’s campaign was derailed when it was publicly revealed that he had accepted expensive suits from Robert Bourgi, an influential business lawyer known for representing African dictators. The suits were valued at thousands of euros, and the public disclosure of this gift severely undermined Fillon’s campaign.

The case of Gerhard Schröder, former Chancellor of Germany, is particularly instructive. Even after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Schröder remains an active member of Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD). A German court has permitted him to keep information about his lobbying activities confidential. Schröder’s post-political career has been closely tied to Russia, especially through his board positions with Nord Stream AG and Russian energy giant Gazprom. The court’s decision to shield details of his lobbying endeavors brings into sharp focus issues related to transparency and potential conflicts of interest within Germany’s political structure.

There is undoubtedly room for improvement, but there is no unmanageable level of corruption that would preclude effective governance within a federation in Central Europe: top officials are not paid Russian agents.

III. External Opposition and Self-Determination

Becoming a geopolitical entity of significance is primarily a function of internal will and capability, not external acceptance or recognition.

The events surrounding the reunification of Germany in 1990 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 illustrate the limitations of external influence over a nation’s destiny. Specifically, France was initially reluctant to support Germany’s reunification due to concerns over a resurgent Germany dominating European politics. Similarly, both France and Germany showed apprehensions about the disintegration of the Soviet Union, fearing the instability that could ensue. Yet, despite their reservations, both events occurred largely as driven by the internal dynamics of the countries involved, rather than external pressures.

German reunification was achieved through both diplomatic negotiations and internal consensus, regardless of French concerns. Likewise, the breakup of the Soviet Union happened due to various factors like nationalist movements, economic crises, and governance failures, which external powers had limited influence over.

Moreover, the subsequent efforts by France and Germany to build closer ties with Russia, particularly in the form of energy partnerships and diplomatic engagements, have not been fully successful in bringing Russia closer to Western norms. This was laid bare by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a move that went against the principles of international law and jeopardized European security.

These examples underscore the premise that the agency for shaping a nation’s future lies within its own boundaries. The skepticism or objections of external powers, however valid, do not have the ultimate say in determining a nation’s course of action or its rise as a power. Therefore, in the context of establishing an Intermarium, Central European countries should focus on their collective will and shared objectives, rather than being overly concerned with external viewpoints that have historically proven to be secondary.

IV. Filling the Western Power Vacuum

As Western Europe and the United States grapple with internal challenges ranging from political polarization to economic stagnation, there exists an opportunity for an Intermarium federation to emerge as a stable and dynamic geopolitical entity in the West. For instance, economic data such as GDP growth rates and unemployment figures reveal ongoing difficulties in Western Europe and the U.S., while many Central European countries have been experiencing robust economic performance.

In terms of military strategy, the concept of “strategic autonomy” in Europe is still debated and remains an aspirational rather than operational policy. Countries like France have particular military focuses, such as anti-terrorism operations in the Sahel region of Africa, that do not align with the defense needs or capabilities of Central European countries, especially concerning the Russian threat on their eastern borders.

By forming a federation, the Intermarium would create a unified military force that could be specialized and streamlined to address specific regional challenges. This would not only serve as a deterrent to Russia but also relieve the United States from being the primary security guarantor in the region. As a consequence, the U.S. could allocate more of its military resources to countering rising powers like China, thereby maintaining a more focused global security posture.

This new configuration would also bring a degree of strategic balance to the West. It would provide an alternative center of gravity in a landscape where power has been predominantly bifurcated between the United States and a heterogeneously aligned European Union. In this setup, an Intermarium federation could act as a bulwark against Russian expansionism more efficiently than a disjointed European strategic autonomy initiative, potentially attracting more concrete American support.

Therefore, an Intermarium federation holds the promise of filling a crucial void in Western geopolitical strategy. By focusing on regional stability and security, it can contribute to broader Western objectives while allowing traditional powers like the U.S. to allocate resources more efficiently.

V. The Intermarium as a Pillar of Regional Stability

The absence of a strong, unified entity in the Central European region contributes to ongoing instability, particularly in relations with neighboring powers such as Russia and Germany. An Intermarium federation would fundamentally alter this equation, emerging as a force to be reckoned with on the geopolitical stage.

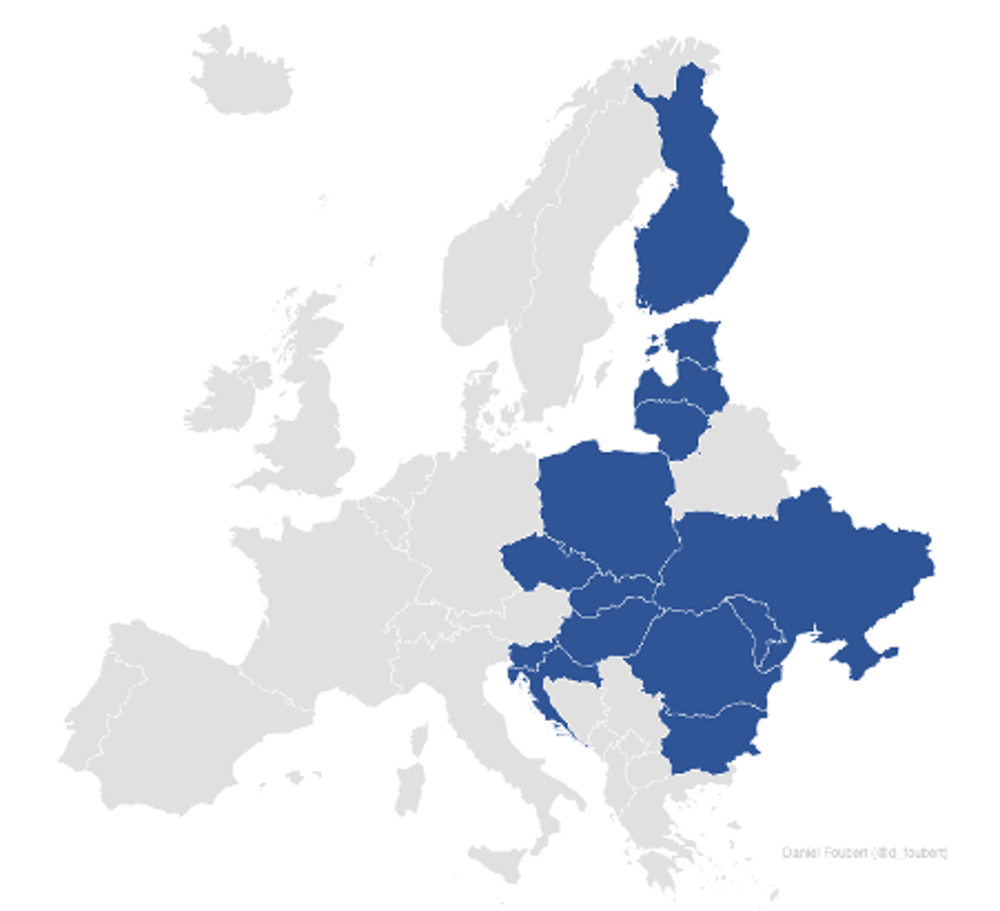

Specifically, let’s examine the combined economic and military prowess of the potential Intermarium nations. According to the 2023 forecast from the International Monetary Fund, the GDP of Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, the Baltics, Finland, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Croatia and Slovenia should total approximately $2.7 trillion. This figure significantly surpasses that of other influential players in the region, such as Russia, with a GDP of around $2 trillion. The Intermarium federation would likely have a combined GDP that would make it one of the largest economies in Europe.

Military capabilities would also be considerably enhanced under a federation. Combining Poland and Ukraine’s military strength with those of other Central European countries would create a formidable force that could act as a deterrence against Russia, with well over 500 000 soldiers, and weapons that would crush any Russian army.

When it comes to territory, the combined landmass would exceed 2 100 000 square kilometers, providing not just a significant geographical footprint but also resources and strategic depth.

Given these figures, it’s evident that the formation of an Intermarium federation would place significant economic, military, and territorial assets under a single flag. This alignment would change the strategic calculus for neighboring powers, providing a strong disincentive against pursuing aggressive policies in the region. In contrast, the current fragmentation encourages larger powers to manipulate smaller countries against each other, exacerbating instability.

VI. Aligning with Systemic Interests

The structure of international relations operates much like any hierarchical society, where stability is a prime concern for the dominant powers. For instance, the United States and China heavily invest in maintaining an organized, predictable global setting because it is essential for their multinational corporations. These corporations are often the most vulnerable to geopolitical fluctuations and disruptions, relying on stable international markets to continue their growth. Disruptions, such as Russia’s actions in recent years, unsettle this status quo and invite counterbalances.

Data from global economic indicators and risk assessments demonstrate that instability has a direct impact on the performance of international businesses. For example, according to the Global Peace Index, countries experiencing higher levels of political instability correspondingly report lower GDP growth and higher insurance premiums for businesses.

Given this backdrop, there is a force that supersedes even the superpowers — the international system itself. This system has an intrinsic interest in maintaining stability to perpetuate economic growth. As such, if a federation of Central European countries under the Intermarium banner proves capable of contributing to this stability, it will gain acceptance from more influential states. This is particularly crucial at a time when some traditional powers are experiencing internal strife or economic stagnation, thereby becoming a source of instability themselves.

VII. Challenges to the Intermarium

Several factors could derail the Intermarium project and exacerbate discord among the participating countries:

1. Of course, nationalistic tendencies in some countries may undermine the willingness to cede authority to a central body, causing divisions among member states.

2. Economic inequality among member states could cause tension. Wealthier nations may be reluctant to share resources with less affluent countries, fearing a drain on their own economies. For instance, Finland has a considerably higher GDP per capita compared to Ukraine.

3. Differences in political ideology, from social issues to economic models, can also pose significant challenges. The socially liberal outlook of the Baltics, for example, may clash with the more conservative ideologies prevalent in countries like Hungary or Poland.

4. The Intermarium countries have varied relationships with external powers like Russia and the United States. Conflicting foreign policy objectives could thwart unified action. For example, Romania and Bulgaria have historically been more pro-Western compared to Hungary’s closer ties with Russia.

5. Disparate defense priorities and commitments can also cause rifts, given various levels of military spending engagement for instance.

6. Past conflicts or territorial disputes could come to the fore and poison diplomatic efforts. For example, Romania and Hungary have tensions regarding the status of the Székely Land, a Hungarian-majority area in Romania.

7. Countries in the region have different levels of dependency on Russian energy. Diverging energy policies could cause disagreements.

8. Lack of public support for federalization could slow down or entirely halt political proceedings, as politicians might be reluctant to advocate for a cause that is unpopular among their electorate.

9. A successful federation would likely require a few dominant countries to lead the process. Without such leadership, the initiative could stall due to a lack of direction or decisiveness.

10. Different countries have different constitutions that may be incompatible with a federal system. Constitutional amendments may be required, which can be a lengthy and politically fraught process.

Understanding these challenges in depth would be critical for any proposal advocating for an Intermarium federation, as they present not only potential roadblocks but also areas that would require careful negotiation and planning.

VIII. Mitigating the Challenges

Here is what we could do to address each one of these challenges:

1. Establish a central economic planning board that has rotating leadership from each member country, focused on macroeconomic stability.

2. Implement a framework for collective decision-making that respects the autonomy and core beliefs of each nation. Start with a smaller group of countries and then aggregate the others, like for instance a Baltic federation or a few smaller federations.

3. Create a unified defense strategy with opt-out clauses for specific military actions that a member country might oppose.

4. Promote multi-lingual education and cultural exchange programs within the federation to foster greater understanding and unity.

5. Pool resources for collective energy security, including investment in renewable energy sources and diversification of suppliers.

6. Maintain separate domestic legal systems while harmonizing laws that have a direct impact on federation matters.

7. Establish an independent, federation-wide anti-corruption agency with the authority to investigate and act on corruption issues in any member country.

8. Develop a two-tiered system of governance where some powers are retained by member states and others are vested in a central authority.

9. Leave to member states the possibility to conduct their own foreign policies to a limited extent.

10. Conduct regular referendums and public consultations to gauge public opinion on key federation policies, ensuring that decisions are transparent and accountable to the population.

Conclusion

In summation, the formation of an Intermarium federation presents a strategically viable and socio-politically coherent addition to the existing structure of the European Union. From the shared cultural heritage to the existing legal frameworks, and from the potential for greater geopolitical autonomy to the positive impact on the international order, the advantages of such a federation significantly outweigh its challenges. In an era marked by flux and the decline of traditional Western powers, Central European nations have an unparalleled opportunity to assert themselves as a stable, harmonious bloc that could mitigate both unbalanced German hegemony in the EU and the Russia security threat. The Intermarium not only has the potential to elevate Central Europe on the global stage but also to reinvigorate the European Union as a formidable global power. Therefore, it is not only prudent but also imperative for Central European nations to seriously consider the possibilities and benefits that the Intermarium can offer.