Introduction

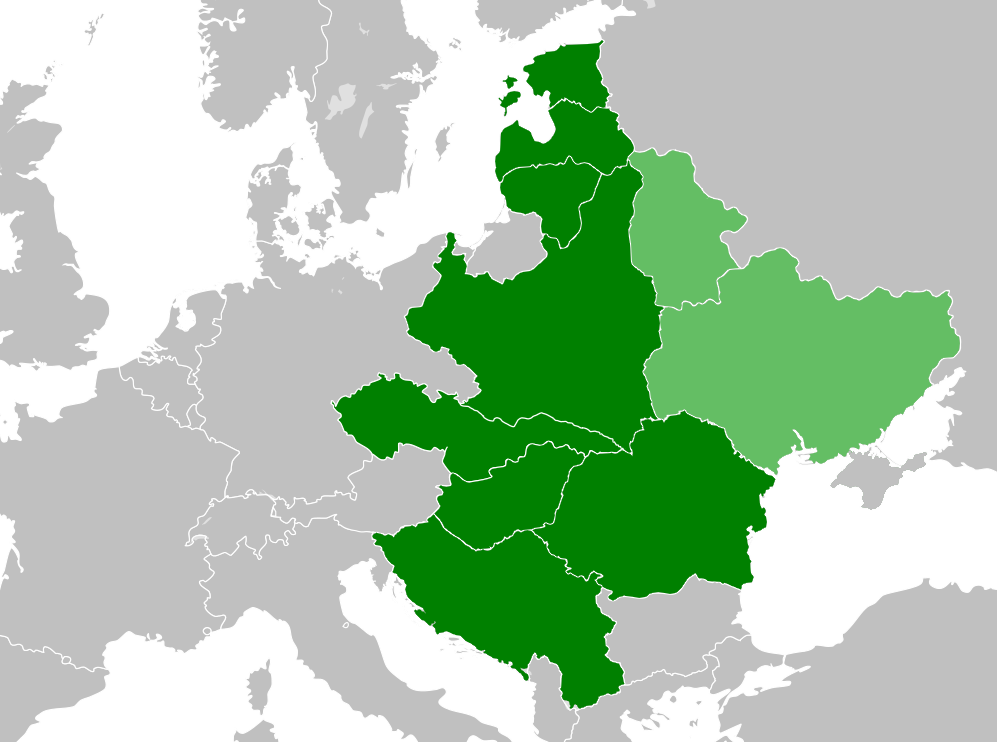

The Intermarium was an ambitious geopolitical concept primarily formulated by Polish statesman Józef Piłsudski. Conceived in the aftermath of World War I, the plan aimed at creating a confederation of Central and Eastern European states stretching from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The overarching goal was to serve as a counterweight to the expansive ambitions of Germany to the west and the Soviet Union to the east.

It wasn’t just a diplomatic or military strategy; it was a vision of collective security and geopolitical balance. At a time when the newly formed or re-established states of Central and Eastern Europe were navigating the perils of emerging nationalism, ideological divides, and territorial disputes, Piłsudski’s Intermarium promised a unified front against external aggression. The initiative aimed to solidify the independence of the states involved and thereby maintain a power equilibrium in the region.

However, despite its conceptual brilliance and potential advantages, the project failed to materialize during the tumultuous interwar period. The initiative faced multiple challenges that ultimately led to its downfall, ranging from ideological divergences among prospective member states to geopolitical realities that made unity difficult. Further complicating matters were a lack of external support from major Western powers and a series of internal political obstacles. Worse than the failure of a project: it was also the failure of the Intermarium as a region and as a group of populations, who were then plunged into the atrocities of the Second World War.

Ideological Divergences

One of the central ideas underpinning Józef Piłsudski’s vision for the Intermarium was the concept of Prometheism. This ideological framework was aimed at destabilizing and eventually breaking up large, multi-ethnic empires like the Soviet Union to liberate the captive nations within. Prometheism was not just a strategy for Polish independence but envisioned a grand reshaping of Eastern Europe, freeing nations from the shackles of imperial dominance. Piłsudski viewed the Intermarium as a tool that would facilitate this liberation, providing member states with the collective power to resist both Soviet and German imperialism.

However, Piłsudski’s Promethean vision was not universally shared among the states considered for membership in the Intermarium. While some nations, such as Estonia and Latvia, shared Poland’s concerns about the Soviet Union, their commitment to the destabilization of larger powers was less pronounced. These countries were more focused on safeguarding their newfound independence than on actively participating in the disintegration of neighboring empires.

Further divergence emerged when examining the ideological frameworks of potential member states. Piłsudski’s Poland was a newly resurrected republic committed to democratic governance, at least initially. Yet, other countries had varying levels of commitment to democratic principles. Czechoslovakia, for example, had established a parliamentary democracy, whereas states like Romania and Hungary were leaning towards authoritarianism. Additionally, the perspective on nationalism and anti-communism differed considerably among these nations. For instance, while Poland and Czechoslovakia might have been apprehensive about the rise of communism, Romania and Hungary were more concerned about territorial disputes with each other.

These ideological discrepancies made it extremely difficult to forge a cohesive and united front. Each nation brought its own set of priorities and concerns to the table, making the consensus on collective action elusive. While Piłsudski’s Prometheism sought to unify these disparate states under a common cause, the actual political and ideological landscape was far too fragmented for such unity to materialize.

Geopolitical Realities

One of the most glaring discrepancies was the threat perception among the prospective member states. Poland, reestablished after the partitions and World War I, considered both Germany and the Soviet Union as existential threats to its sovereignty. For Warsaw, the Intermarium was a necessary strategic depth, a buffer against two historical aggressors.

However, not all potential member states shared Poland’s dual threat perception. Countries like Czechoslovakia and Hungary were primarily preoccupied with each other and their surrounding neighbors. For Czechoslovakia, the more immediate concern was the German-speaking Sudetenland within its own borders and Hungary to the south, rather than the distant Soviet Union. Hungary was primarily focused on revisionist aims to recover territories lost after the Treaty of Trianon, particularly those in Romania and Czechoslovakia. Such parochial focus on immediate neighbors diluted the potency of any unified front against Germany and the Soviet Union.

The geopolitical landscape was further fragmented by territorial disputes among potential member states. For instance, Romania and Hungary had deeply rooted conflicts over Transylvania. These territorial disputes were not mere footnotes; they were pressing issues that often took precedence over any unified foreign policy against larger external threats.

Polish-Ukrainian relations serve as another example of the complex territorial and ethnic disputes that plagued the Intermarium concept. Both Poland and Ukraine had territorial claims over the region of Eastern Galicia, which had a mixed population of Poles and Ukrainians. This dispute was not just a matter of borders; it also carried significant ethnic and nationalist undertones. While Piłsudski, in line with his Promethean outlook, had hoped for an alliance with non-Russian ethnic groups within the collapsing Russian Empire, the reality on the ground proved less conducive. A series of conflicts between Poland and Ukraine, including the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919), had already poisoned relations between the two nations. The territorial dispute over Eastern Galicia further deepened the mistrust and made the prospect of a Polish-Ukrainian alliance within the framework of the Intermarium highly unlikely.

Following the strained relations due to territorial disputes over Eastern Galicia, an attempt to improve Polish-Ukrainian relations came in the form of the Treaty of Warsaw in April 1920. This treaty, signed by Poland and the Ukrainian People’s Republic led by Symon Petliura, aimed to create a military alliance against the Soviet Union. It promised mutual assistance and envisioned a federated Poland and Ukraine after the war. While some coordinated military operations did take place, the alliance fell short of its broader aims.

This brief and ultimately unsuccessful alliance was further complicated by the Treaty of Riga in 1921, which brought an end to the Polish-Soviet War. This treaty had long-lasting implications for Polish-Ukrainian relations. It divided Ukrainian territories between Poland and the Soviet Union, cementing the partition of Ukraine and fueling resentment among Ukrainians. The Treaty of Riga thus solidified divisions and soured the possibility of a cooperative Polish-Ukrainian relationship within the framework of the Intermarium.

In addition to disputes between Romania and Hungary and the complex relationship between Poland and Ukraine, the Teschen dispute between Poland and Czechoslovakia further exacerbated geopolitical tensions. Teschen, an ethnically mixed region rich in coal deposits, was claimed by both Czechoslovakia and Poland. The tension reached a breaking point with the Polish-Czechoslovak War of January 1919, although hostilities were relatively brief. The subsequent division of the region did little to settle nationalist grievances and left both nations with lingering animosity.

Another obstacle that stymied the Intermarium project was the persistent territorial dispute between Poland and Lithuania over the region of Vilnius (Wilno in Polish). Following World War I, both nations laid claim to the area, a contention that became more acute after Polish forces captured Vilnius in 1920. Lithuania considered this an act of aggression and severed diplomatic relations with Poland, maintaining a state of “no war, no peace” throughout the interwar period. This fracture between Poland and Lithuania crippled the notion of a cohesive Central and Eastern European alliance. The Vilnius question polarized these key prospective members and demonstrated the degree to which historical grievances and territorial ambitions could undermine the larger goals of regional stability and cooperation.

This fragmentation severely hampered the formation of a cohesive Intermarium alliance. Each country came with its own set of geopolitical complexities that could not be easily set aside for the broader vision of collective security against larger external threats. While Piłsudski envisioned a bloc that would function as a unified counterweight against imperial ambitions, the actual geopolitical calculations of potential members were far too divergent to allow for the formation of such a bloc.

In this context, it’s also worth mentioning the Little Entente, an alliance formed in the 1920s among Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Unlike the Intermarium, which aimed for a broad coalition to counter both Germany and the Soviet Union, the primary purpose of the Little Entente was to serve as a counterbalance to Hungary and to secure the territorial integrity of its member states. Czechoslovakia, a potential key player in any Intermarium coalition, was more invested in this alliance. This alignment presented a conflicting set of priorities and limited Czechoslovakia’s enthusiasm for the Intermarium project. The existence of the Little Entente further fragmented the geopolitical landscape and offered an alternative set of alliances that competed with the Intermarium for diplomatic attention and resources.

Lack of External Support

Another critical factor contributing to the failure of the Intermarium project was the lukewarm attitude from major Western powers. Both France and the United Kingdom, while they had significant influence in the geopolitics of Europe during the interwar period, were hesitant to back the Intermarium concept fully. Their hesitancy stemmed from a strategic calculus; supporting a coalition aimed at countering Germany and the Soviet Union could risk antagonizing these powers and destabilizing the fragile balance of power in Europe.

France had complex motivations when it came to the Intermarium. On one hand, France had a vested interest in containing German power and was, therefore, initially sympathetic to any alliance that could serve as an eastern counterweight to Germany. On the other hand, France had already committed itself to other regional security arrangements, most notably the Little Entente, which aimed at constraining Hungarian and, indirectly, German ambitions.

Furthermore, Although France had a military alliance with Poland, it was also keen to avoid upsetting relations with the Soviet Union, especially as concerns about German militarism grew throughout the 1930s, particularly as conversations about collective security arrangements against Germany began to take shape in the League of Nations. Thus, despite some early enthusiasm, France’s support for the Intermarium was lukewarm at best. Its dual aims of not upsetting the Soviets while also containing Germany led to a cautious and ultimately non-committal stance towards the Intermarium, depriving the initiative of a powerful western ally that could have lent it significant diplomatic and possibly military support.

The United Kingdom, too, was wary of committing to a project that could provoke Germany. British foreign policy of the time was characterized by a policy of appeasement toward Germany, in the hopes of averting another major conflict. As a result, the U.K. was not inclined to back a coalition that might be seen as a direct challenge to Germany, a country it was trying to diplomatically engage: any challenge to Germany’s dominance of the region had to be smothered in order to keep good relations with the German government.

Across the Atlantic, the United States was not a significant factor in the Intermarium equation either. The U.S., during most of the interwar period, was in a phase of isolationism. Following World War I, there was a strong sentiment within the United States against becoming embroiled in “European entanglements.” The U.S. was focused inward, dealing with the economic implications of the Great Depression and the societal changes of the era.

The absence of robust external support severely weakened the Intermarium’s chances of becoming a reality. Without the backing of major Western powers, the prospective member states were even more reluctant to commit to the project. They saw it as too risky and geopolitically fraught, lacking the international backing that could offer a counterbalance to German or Soviet aggression.

Internal Political Challenges

Even if one were to overlook the ideological and geopolitical hurdles, the Intermarium concept was further compromised by a series of internal political challenges within the prospective member states. These states were dealing with their own domestic issues, including regime changes, political instability, and internal divisions, which made the prospect of entering a geopolitical alliance even more complicated.

For instance, Poland itself underwent significant political changes during the interwar period. The death of Józef Piłsudski in 1935 was a turning point for Polish foreign policy. Piłsudski was the principal architect and the most fervent advocate of the Intermarium concept. His death left a vacuum in Polish political leadership and introduced an era of uncertainty in foreign policy direction. The shift towards a more nationalist and less cooperative stance by Piłsudski’s successors had implications for the Intermarium, effectively weakening Poland’s commitment and capacity to push for the initiative.

Similarly, other potential member states were grappling with their own internal issues. Hungary was moving towards an authoritarian regime under Miklós Horthy, while Romania was facing its own set of political challenges, including the rise of the Iron Guard, an ultranationalist and anti-Semitic movement. Czechoslovakia was wrestling with ethnic tensions among its Czech, Slovak, and German populations. Each of these situations created an internal focus that often took precedence over external alliances.

In essence, the internal political landscapes of the potential member states were in a state of flux, characterized by regime changes and internal discord. These domestic challenges made it exceedingly difficult to galvanize support for a cohesive and committed Intermarium alliance. It also complicated diplomatic efforts, as frequent changes in political leadership led to inconsistent foreign policies among the would-be members.

The economic instability that marked the interwar period had also a significant impact on the feasibility of the Intermarium project. The global economic turmoil of the 1920s, culminating in the Great Depression of the 1930s, left many prospective member states economically vulnerable. High unemployment rates, coupled with rampant inflation in countries like Germany and Austria, spilled over into the economies of Central and Eastern Europe.

Poland, still grappling with the economic consequences of recent wars and territorial adjustments, found itself economically isolated. Czechoslovakia and Hungary, on the other hand, were focused on their economic recovery and were wary of any alliance that might drain their resources further. This economic frailty made the prospect of pooling resources for a mutual defense pact less attractive and heightened the internal divisions as each country prioritized its national economic recovery.

While the political elites debated the merits and flaws of the Intermarium concept, public opinion in the potential member states was often divided or even apathetic towards the idea. In Poland, the public was generally more preoccupied with immediate economic and social concerns than with the grand geopolitical visions like the Intermarium. Likewise, in states like Czechoslovakia and Romania, nationalistic fervor often overshadowed the potential benefits of a multinational alliance, as many were skeptical about partnering with historical rivals or ethnically diverse neighbors.

These societal attitudes contributed to the lack of a robust public mandate for politicians to push forward with the Intermarium plan. Given the already complex web of ideological and geopolitical challenges, the lack of popular support further undercut any momentum the Intermarium concept may have had.

In conclusion, the Intermarium’s failure was not just the result of ideological divergences or external geopolitical challenges. It was also critically undermined by the internal political realities of the countries it aimed to unite.

Consequences of Failure

The failure of the Intermarium concept led to the cataclysm of World War II. The absence of a strong, cohesive alliance in Central and Eastern Europe left the region vulnerable to external aggression and ultimately led to disastrous outcomes for many of the nations involved.

With the Intermarium concept unrealized, individual states found themselves isolated and ill-prepared to resist the rising tide of German and Soviet expansionism. Poland, the primary architect of the Intermarium, was the second to feel the consequences. In September 1939, Poland was invaded from both sides: Germany attacked from the west and the Soviet Union from the east. The dual invasion led to the partition of Poland, fulfilling the worst fears that had initially inspired the idea of the Intermarium as a defensive alliance. Poland’s partition served as a precursor to further occupations and partitions within the region.

Likewise, the absence of a united front made it easier for the Soviet Union to assert its influence over the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. These countries, which had been considered as potential Intermarium members, were forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940 under the conditions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Countries like Czechoslovakia and Hungary, too, faced the brunt of regional “instability”. Czechoslovakia was dismembered, first through the Munich Agreement that allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland and later with the occupation of the remaining parts. Hungary initially gained territory through its alliance with Nazi Germany but eventually found itself occupied and its sovereignty compromised.

In essence, the failure to establish the Intermarium alliance left the countries of Central and Eastern Europe without a collective defense mechanism, making them easy targets for stronger, expansionist powers. The vacuum created by the Intermarium’s failure was filled by the brutal realpolitik of World War II, leading to occupation, partition, and immense suffering for the people of the region.

Conclusion

The Intermarium, a visionary concept aimed at uniting Central and Eastern European states against external aggressors, faltered due to a host of factors that could not be reconciled during the interwar period. Ideological divergences among the prospective member states, ranging from differing commitments to democracy and nationalism to conflicting anti-communist stances, sowed discord from the outset. Geopolitically, the myriad of territorial disputes, such as those over Eastern Galicia and Teschen, further fragmented relations. The diverging threat perceptions of the individual states—most notably Poland’s focus on both Germany and the Soviet Union versus the narrower concerns of countries like Czechoslovakia and Hungary—added another layer of complexity. External support was also conspicuously lacking. Major Western powers like France and the United Kingdom were hesitant to back the initiative, fearing it could antagonize Germany and the Soviet Union. The United States, largely isolationist during this period, failed to offer substantial assistance. Internal political dynamics, including regime changes and Józef Piłsudski’s death in 1935, further undermined the viability of the Intermarium.

Modern initiatives like the Three Seas Initiative can learn valuable lessons from the failure of the Intermarium. Creating a successful alliance demands more than just a shared sense of external threat; it requires ideological coherence, diplomatic finesse, and the committed backing of both internal political systems and external powers. The failures of the Intermarium serve as a stark reminder that good intentions and common fears are not enough; comprehensive planning, robust diplomacy, and, above all, a unified vision are the key elements for the success of any regional alliance. By studying the pitfalls that undermined the Intermarium, today’s geopolitical alliances in Central and Eastern Europe have a historical roadmap of what to avoid. This could prove invaluable for fostering more successful cooperation in a region still characterized by complex national interests and external pressures. Even today, our ability to defend ourselves against Russia and not to be manipulated by Germany’s “business projects” (as Chancellor Olaf Scholz called the Nord Stream 2 pipeline) depends on our regional cohesion and ability to stay united